We all work for the IMF now. And if you haven’t realized that yet, I urge you to wake up to your new condition so you will not be caught unprepared. The sooner we all realize that, the smaller (hopefully!) the shock will be.

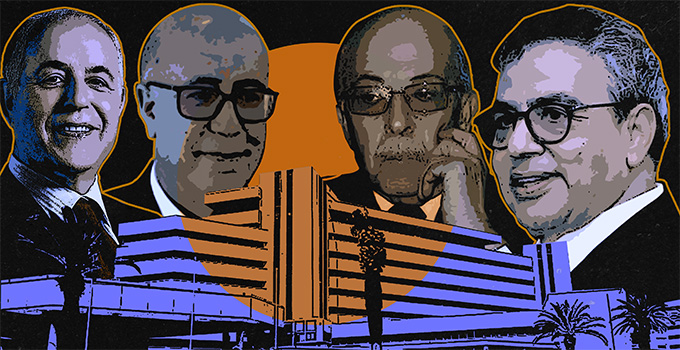

We’ve been aware of this for quite some time now, but since Mehdi Jomaa took office few weeks ago, it is striking how the public mood was gradually geared and prepared toward the acceptance of this fact as an inescapable fatality. And the pseudo-Experts (guess who!) who were condemning prices increase for as long as I can remember, magically turned austerity hawks overnight and preached tirelessly its virtues and how IMF’s structural reforms will bring us wealth and prosperity so we will all live happily ever after!

After listening to Mehdi Jomaa interview last night, I had the strange feeling that he was not in control of anything (which is true, at least on the economic front!). And it looked as if he was told what to say and he obediently said it. My takeaways from the interview are the following: the government can not, will not and should not help us. From now on it’s and individual game and everyone is out for himself.

The humiliating letter of surrender that have been sent to the IMF by our economy minister Mr. Hakim Ben Hammouda is the ultimate proof that we, and especially the poor, have been abandoned by the government. Case in point, there is an astonishing passage in that document that have been overlooked. In page 10 the minister makes (or have been told to say so by IMF’s so-called experts…take your pick!) a commitment to suppress the interest rate cap for commercial loans and to increase it for individual borrowers:

Modify the excessive borrowing rate by removing the ceiling for loans to businesses and increasing it for loans to private consumers. In March 2013 we eliminated the ceiling on deposit rates for term deposits that had been introduced in December 2011. We expect to do the same with regard to lending rates by amending the legislation on the excessive interest rate, which will be eliminated for companies and initially increased for individuals. This will allow the banks to mobilize more deposits without harming their profitability margins and to apply a higher interest rate to high-risk clients, thus improving monetary policy transmission channels. To this end, an impact study—to be conducted with World Bank TA— will be finalized by March 2014 (structural benchmark). Tunisia: Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, and Technical Memorandum of Understanding. , page 10.

This means that from now on banks could charge its commercial customers any rate it wishes as long as the latter is willing to accept. Of course the effect of this measure on big firms will relatively be small, since they have enough leverage over banks to negotiate descent rates. So, the victims of this measure will mostly be small businesses who do not have that kind of negotiating power.

To put things in perspective, let’s consider a simple example. But before doing so, let me remind you that the current maximum rate is about 10% (give or take few percentage points). This means that if a firm gets a loan of one million dinars at that rate with a 10 years maturity, it will end up paying two million dinars. That is, one million dinars as principal and another million dinars as interests. Now, suppose there is no interest rate cap and the bank choose to charge its client rather 15% rate. In this case the firm will end up paying an extra half million dinars. Indeed, if we suppose (for simplicity) an in-fine loan, the bank’s cash flows related to this credit will look something like this:

But what if the rate charged reach 20% or 30? Wouldn’t that prohibit small borrowers from ever getting a loan? And wouldn’t that drive the aggregate supply down pushing us further into the current slump?

For individuals, however, the implementation of this measure will translate into a systematic increase of interest rates paid by a large part of consumers (car loans, mortgage loans, etc.) because it is more than likely that the banks will collude in order to charge higher rates. Hence, this measure, which we might as well call loan sharking, will almost-surely harm consumers, firms and society alike. But, hey, that’s not what really matter for the IMF (especially poor people).

Now, someone may say that this reform is put in place to promote competition and provide capital for risky projects. But the truth is far from that. Indeed, first of all, there is no queue of entrepreneurs with highly risky and highly profitable projects in fronts of our banks and who could not secure loans because of interest rate cap. Second of all, even if that is true and beneficial for firms, there is no economic, financial, or even moral justifications to increase interest rates for already fragile consumers!

To me, the sole purpose of this measure, which is one of IMF’s structural reforms, is to prevent a banking crisis similar to the liquidity crisis of 2012. Indeed, by allowing banks to extract more rent from the society will strengthen the financial system and reduce the systemic risk that could jeopardize Tunisia ability to payback its debt. So the IMF must ensure the banking sector stability and profitability even if it means sucking consumers and firms dry!

This is obviously the first round of the so-called structural reforms we’ve been promised. And so far it does not look good. My fear is that what is coming next (public banks partial or total privatization, compensation fund suppression, etc.) will dwarf the previous one and open up the door for a Tunisian episode of IMF riots. So, stay tuned!

[…] se positionne comme son pendant au niveau microéconomique et sera de ce fait le faire valoir du FMI dans la promotion des Partenariats […]

[…] j’ai dis que désormais nous travaillons tous pour le FMI ça n’était pas une exagération. Il suffit juste de bien interpréter les signaux envoyés […]