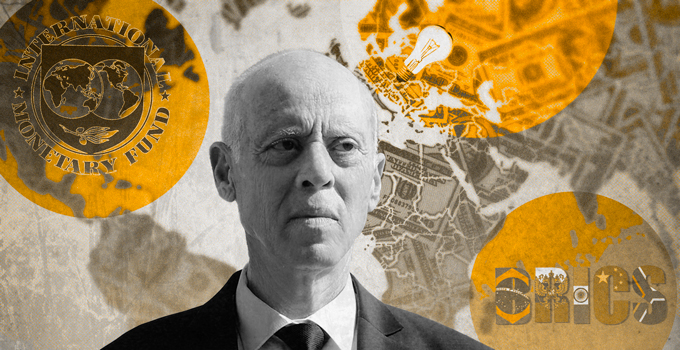

A few simple words have pulled the economic dilemma back into the arena of political debate. On April 6, Kais Saied stood before the tomb of his predecessor and Tunisia’s first president, Habib Bourguiba. Having agreed to address journalists covering the event, he was questioned about the fate of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Saied’s rejection of IMF injunctions was categorical: « As for the IMF, foreign diktats which only lead to further impoverishment are unacceptable », he stated, subsequently proposing that Tunisians « count on themselves ».

Eastern alternatives?

With this position made public, a number of July 25 supporters called upon authorities to break with the West and seek out IMF alternatives to the East. An acronym quickly made its way into the debate: BRICS. Much like the G7, this grouping of five countries organizes annual meetings to strengthen economic cooperation among member states. Founded in 2009 by Brazil, Russia, India and China, the BRICS integrated South Africa among its ranks in 2011. Its member states are the world’s leading emerging economies who recently surpassed G7 countries in terms of GDP for the first time.

This performance seems to have accelerated the BRICS’ ambition to represent an alternative to Western-dominated institutions (IMF, OECD, etc.), notably through challenging the power of the US dollar. In this regard, China and Russia have increased the volume of their exchanges in yuan, with the effect that the Chinese currency has surpassed the US dollar in the Moscow Exchange. These historical shifts have encouraged countries such as Algeria to request admission into the BRICS. It is undoubtedly this example which has inspired hope, among those close to the current regime, that Tunisia might follow in the steps of its sister country.

Beyond the exaggerated statements of July 25 supporters who claim that the IMF has accepted their request to soften loan conditions for Tunisia, or that the BRICS member countries have decided to admit Tunisia into the group, the scenario is richly informative about divisions within the country’s executive branch. On the one side, a government loyal to the path of its predecessors. On the other, a president whose conception of economy is radically divergent and based on questionable assumptions.

The IMF dilemma

Since the end of July 2021 and well before the inauguration of the Najla Bouden government, Kais Saied appointed Sihem Boughdiri Namsia to head the Finance Ministry. Namsia resumed discussions with the IMF. The country’s Finance Law of 2021 was elaborated with the built-in assumption that Tunisia would receive an IMF loan, prelude to other bilateral loans. The Law included requirements imposed by the Bretton Woods agreement, such as accelerating the reduction of fuel subsidies. In spite of a staff-level agreement reached in October between Tunisia and the IMF, the country was removed from the institution’s December agenda. Nevertheless, the Finance Law of 2023 once again follows IMF recommendations to end fuel subsidies before the end of the year, and to reduce food subsidies by one-third.

Finance laws, which have taken the form of decree-laws since July 25, 2021, are signed by the president. One reform requested by the IMF regarding the legal framework for public companies was approved by a ministerial council, whereas no decree-law has yet been issued to realize this reform. In December, Economy Minister Samir Saied reiterated that there was no alternative to the conclusion of an agreement with the IMF. Several days after the president’s cutting remarks vis-à-vis the Washington-based institution, the same minister, accompanied by the head of the Central Bank, visited D.C. to attend the IMF and World Bank’s Spring Meetings.

At the presidential palace in Carthage, an entirely different tune is played. Kais Saied, whose tepid interest in economy is no secret, deems Tunisia capable of managing without any external—and especially Western—aid. One fundamental idea guides his perception in this regard: the country would be rich were it not for corruption. In December 2020, he set up a commission to restitute funds misappropriated by the former regime and hidden in foreign banks. This initiative, however, was undertaken too late. Switzerland, for instance, where some of this money was possibly stashed, cannot freeze such funds after a period of ten years.

Saied’s magical thinking

When he assumed full power after July 25, Saied had two economic hobbyhorses: cracking down on contraband and speculation, and restituting stolen money. In the first case, we have already witnessed the initial results of the battle waged against speculation (cf. Nawaat Magazine « Le nouvel ordre Saiedien »). In the case of embezzled funds, Saied’s starting point was to insinuate that former Finance Minister Ali Koôli under the Mechichi government had « taken off with the till ». He then commissioned an audit of debts incurred during the post-revolution decade in order to uncover possible kickbacks pocketed by Tunisia’s leaders between 2011 and 2022. Authorities refused to make public the conclusions of this work. Indeed, in the absence of any political communication regarding « those who plundered the country » or undertaking of legal action, it seems unlikely that this work would have been conclusive.

But the standout element of Saied’s theory is criminal reconciliation, an agenda that he has pursued since 2012. Transformed into a decree-law on March 20, 2022, criminal reconciliation is considered by the president to constitute an important aspect of « the country’s real independence ». This principle is based on the findings of the National Commission to Investigate Corruption and Embezzlement, or what is referred to as the Abdelfattah Amor Commission.

The Commission’s report highlights different mechanisms which permitted those close to the former regime to increase their wealth (fictitious jobs, toxic loans with no guarantee, etc.). In the eyes of the president, the issue is not what the state stands to regain, but, simply, embezzled funds. And this is where Saied’s economic vision is fundamentally flawed. While the Commission’s report does not quantify exactly how much the state stands to regain, Saied uses an estimate provided by Salim Ben Hmidane who served as Minister of State Property between December 2011 and January 2014. The president assumes this number, an estimated 13.5 billion dinars, to constitute embezzled funds and to be the direct result of corruption during the country’s « black decade ».

Decree-law 2022-13 sets up a National Criminal Reconciliation Commission that is directly affiliated with the presidential office. It is tasked with examining the case files of corrupt parties, upon its own initiative or at the request of those concerned. Amnesty is proposed for « any physical or moral person […] who committed acts possibly leading to economic and financial violations » before March 20, 2022, whether or not that person ever received a sentence. When discussions with the IMF broke down in December, Saied accelerated the Commission’s set up and tasked its members with « returning the people’s money » within a period of six months. But the Commission fumbled with legal questions and even more so the issue of expediency. Aside from the fact that the principal members of the Ben Ali/Trebelsi family were either overseas or deceased, few individuals would benefit from concluding an agreement with the government now that ten years had already passed. Far from rethinking his strategy, the president rushed headlong into it, dismissing the Commission’s president and denouncing the obstacles arising from within the state apparatus.

As for those close to the current regime, they are either pushing for alternative solutions like the BRICS grouping, or else propagating fanciful theories about gigantic oil basins. Such magical thinking stems from intellectual laziness. As pertains to the BRICS, even if the will to propose an alternative to Western systems is very real, there is no indication that West’s Eastern competitors are philanthropic societies eager to break with the neoliberal order. Not one of these countries has extended any kind of loan to Tunisia since July 25, 2021. A study by the Tunisian Observatory of Economy observes that under the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA, a mechanism which presents itself as an alternative to the Bretton-Wood system), 70% of the allowable quota for each country is contingent upon reforms negotiated with the IMF.

With Tunisia stuck in the mire of economic crisis, its executive branch remains torn between two sides. On the one, a government pursuing the path of austerity. On the other, a president who proposes unexamined solutions and promises paradise, whose vision of economy is conspiracy-inspired. In either scenario, the bill will be paid by none other than « the people », the keystone element of Kais Saied’s agenda.

In my view the article fails to question the arguments put forward by the Government and Saied. The author kept describing rhetoric and actions without questioning and refuting them. ‘Magical thinking’ and ‘flawd’, for example, do not explain.

“One fundamental idea guides his perception in this regard: the country would be rich were it not for corruption.”

There is no attempt to demonstrate the ‘corruption’ is no the fundamental cause of the weak capitalism of Tunisian. After all, there is corruption in the advanced capitalist countries.

There is no attempt to go beyond the mainstream arguments by dealing with the form of capitalism in Tunisia, investment, what produced and for whom, who controls what, i.e. the owners of capital and class relations, unfair-exchange, exploitation, productivity, etc. etc. What is Tunisia to the European Union, for example? Is it an equal partner? It is not. And we need to frame that with the Western European capitalism.