Friday, April 29th, charted buses from l’Institut Français headed for Gafa to assemble at the 6th Youth Forum, which each year, celebrates decentralized cooperation between France and Tunisia. After 5 previous sessions held in either Tunis or Monastir, the choice of “decentralizing” the forum by relocating to Gafsa was motived by the desire to better include Tunisian civil society of interior regions. Hence, out of 200 young participants, half were from southern governorates: Gafsa, Tozeur, Kasserine, Sidi Bouzid, Kebili. Others coming from the remaining Tunisian governorates, France, Algeria, Morocco, Libya, and even Senegal.

While other venues situated closer to downtown were originally what coordinators from l’Institut Français had in mind, Jugurtha Palace, a five-star hotel protected by a security apparatus on the outskirts of downtown, is where the majority of the forum’s events took place.

A pleasant setting – complete with a pool, greenery, and the sound of birds chirping which contrasted the setting of the rest of the city, in addition to creating the background for numerous amounts of selfies taken by participants.

Training and employability of youth are the priority this year, and its true that these themes have a certain resonance in a region such as Gafsa, where the rate of youth unemployment, notably those with college degrees, is record breaking. Moreover, a few kilometers from the hotel, in front of the Gafsa governorate building a sit-in comprised of unemployed youth has been going on for more than six months. But they of course, wont be participating in the forum

“Today, states can no longer do it all ”

Upon arriving Friday afternoon, participants pick up their canvas tote bags and return to their respective rooms at the hotel. Afterwards, they participate in the first session of workshops. The evening is reserved for inaugural discussions, followed by a catered reception. Ministers, councilors, governors, as well as Tunisian and French elected officials follow one another into the dining area, revamped specially for the event. Local representatives enthusiastically welcome the choice of Gafsa, “a region with strong potential for economic development” or even, “a marginalized region in search of positive change”. The French and Tunisian politicians in attendance highlighted the “common challenges” that the two countries face – notably terrorism and climate change. “We’re in the same boat” was the idea that echoed time and time again (one can ironically ask if such a statement is a sort of homage to the migrants lost at sea). What commonly followed were professions of faith in “the youth” who are the wielders of hope. Since after all, “it’s the youth who innovate”.

But the most symbolic discourse is perhaps that of Agnès Rampa, president of the commission Euroméditerranée of the regional council in Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur. Her words at times reflected a brand of cooperation which subscribes to a particular heritage and neoliberal bias. Agnès begins by making note to the audience of her joy of being in Tunisia. Born in Algiers as a pied-noir (French citizen born in Algeria during colonial rule) she affirms that she feels “at home” on this side of the Mediterranean. She praises the Tunisian revolution for having so rapidly reached a “true democracy” and decentralization, an area in which the French are “of course, a few steps ahead”. But the key statement is without a doubt, the following:

“Today, states can no longer do it all. Its thus necessary to facilitate private corporations in Tunisia, like in France – where there remains, despite improvement, people skeptical and weary of “change”.

The state’s limitations also create the backdrop of an “Agora” from Saturday morning. The meeting was devoted to “Youth Employment: What Civil Society Can Do”, articulating three “spaces of dialogue”. Presented as special spaces of discussion between young people, it was moreso three panels or expert debates with representatives from local institutions, French and Tunisian politicians, and members of youth operated initiatives, followed by questions from the audience – cut short by a pressing time constraint.

The first panel addressed professional training with a utilitarian vision. It brought to light that university curriculum should better correspond with the demands of the job market. For instance, do we really need so many philosophy majors? The second advocated for “entrepreneurial support for youth”. It was an opportunity to polish new entrepreneurial lingo with terms such as “social and technological innovation” “launching a tech-business” and “incubator”.

Lastly, the third panel focused on the employment of youth by youth and sought to be a discussion “between youth with the self-made spark and those who are seeking out the same” i.e. the local chapter of l’Union des Diplômés Chômeurs (UDC). Seeing as it was already lunch time, attendance was scarce. The representative from UDC argued that we cannot talk about employment without first addressing the question of development. After numerous presentations of innovative start-ups by ambitious and self-sufficient youth, his calls for mutual aid and will to take on the question from a political standpoint sounded a bit odd. It nevertheless raised a crucial question: For youth, is the only option to attain dignity to create an enterprise? Regardless, the few who were still in attendance were left famished.

A particular mold?

In any case, the youth forum was not conceived for the sake of debating core issues or for political discussion. It was more so destined to enhance “projects” put forth by Tunisian civil society. As a result of the forum, 12 projects were selected, “accompanied” by Lab’ESS (Laboratoire d’Economie Sociale et Solidaire). Among this group, the best could have their shot at a financial endorsement from l’Institut Français.

The forum’s ten themed workshops attributed to drafting projects. They aimed to “propose concrete solutions to the expectations of youth living in the interior regions.” By merely reading their descriptions, interspersed with generic hash tags (#innovation, #socialbond), one can see the underlying ideology. For instance, it was said that “the notion of strong development is far too often placed in opposition with the idea of global economic competition” or that “culture can resolve the issue of employability”. The issues were taken on from an angle emphasizing the efforts of the individual, as if the possibilities of collective efforts were immediately out of the question.

Each workshop brought together around 10 or 15 participants. They were led by laureates from previous years, with support by volunteers from Lab’ESS. The workshops were structured with games and role-play activities. Introductions began with ice breakers where everyone chose an object that symbolizes their personality. People then wrote their expectations on post-it notes before placing them on a PESTEL diagram (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal factors) that would later influence their projects.

Some participants seemed a bit thrown off and had a hard time expressing themselves in French. Others, having already gone through with projects with organizations such as l’AFD (Agence Française de Développement) and PNUD (Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement), were well versed in the cooperation jargon – “capacity development”, “upgrading”, “management”, “structural analysis”, and (again) “incubation”. By having a better understanding of the objectives of the workshop, they were visibly more confident of themselves than other participants.

The lingering question one asks oneself is if those who play their cards right and score the funding will be the ones who know how to better adapt to the “culture” of cooperation or if it will be those who truly have the most innovative, realistic, pertinent ideas that are most attuned to the local context.

Cooperation and its Discontents

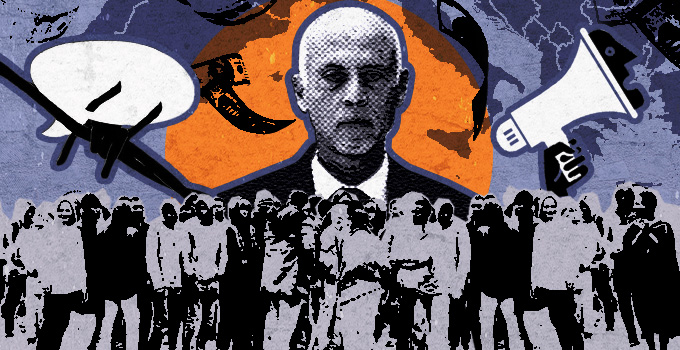

Upon leaving the youth forum, its difficult to not feel a bit of discomfort in light of certain aspects which, beyond the forum itself, taint the world of cooperation. The first concerning issue is the use of words. If terms such as “forum” “dialogue” and “agora” suggest a certain level of openness, deliberation practices, or even direct democracy in fact, then nearly everything in the youth forum is controlled by the organizers. The profile of participants – selected in advance in addition to the execution of activities, agora-esque workshops, the intervention content. At no point in time is there space for a debate that allows conflicting viewpoints or arguments be brought to the forefront – which is the basis of democracy. The various events of the forum are carried consecutively without a hitch. Whereas the discourses, models, and manners of performing what is predetermined in advance for the three days are instilled with more or less resistance in the spirits of participants.

The hundreds of youth present and this forum are already implicated in Tunisian or international “civil society”. One can imagine that once returned to their communities, they will influence those that surround them. Many of them will without a doubt reproduce “best practices” that they had witnessed in the forum without questioning them. As such, and the heart of the “interior” regions of Tunisia, one is put in contact with members of local associations donning a Che Guevera-esque beret, who explain to their interlocuters that its always necessary to try hard to achieve SMART objectives (defined as Specific, Measurable, Acceptable, Realistic, Temporal) which they learned in such and such program reinforcing civil society. This type of management tool is not neutral. It is based on the need of a pragmatism, that while is not a necessarily a bad thing, it is nevertheless accompanied by the diffusion of a neoliberal ideology, in addition to celebrating networking, flexibility, and project organization.

This emphasis placed on a concrete initiative neglects the political scope, where young civil society could also potentially play a role. In doing so, in certain ways it legitimizes Thatcherian assertions according to which “there is no political alternative to liberalism”. Behind the “support” of civil society, which aligns itself with cooperation programs, the dissemination of a doctrine takes shape. By laying it on a bit thick, this doctrine pretends that what will help boost start-ups is a solution to mass unemployment and marginalization. However, the rules of the game including the internal race between innovative projects implies that in this forum there are winners and losers….in light of some “success stories”, how many are left behind?

iThere are no comments

Add yours