Decree-Law 88 guarantees « the liberty of forming, adhering to and exercising activities within associations, and the reinforcement of the role of civil society organizations as well as their development and respect for their independence ». For those who had poured their efforts into protecting this measure, the dizzyingly swift adoption of draft law 30/2018 was like a carpet had been pulled out from beneath their feet. Talks between associations and the Ministry of Civil Society and Human Rights had been underway for more than a year ever since then-Minister Mehdi Ben Gharbia had pushed to modify the decree-law on the basis of its unconstitutionality. Article 65 of Tunisia’s 2014 Constitution stipulates that the organization and financing of associations are to be adressed through organic (as opposed to ordinary) laws. In spite of the Minister’s promises to safeguard liberties and consult civil society organisations regarding reforms in the sector, the latter feared that proposed changes would ultimately translate into a restriction of liberties.

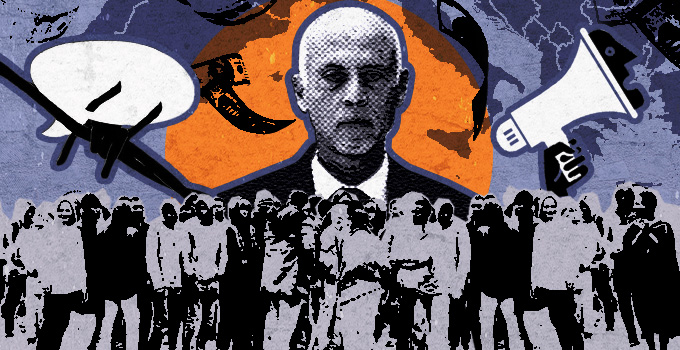

Civil society pushes back against efforts to « improve » sector regulations

Such concerns were widespread and had echos in Washington, where US Congress quickly caught wind of proposed reforms. According to the American think-tank Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), Congress had requested information concerning a draft law destined to replace Decree-Law 88, although such a text had never been made public. In the meantime, the US State Department granted funding to Democracy International for its Improving the Regulatory Environment for Civil Society Organizations Project. POMED reports that the US embassy in Tunis « elected to fund this project after concluding that the United States could not prevent the passage of a new NGO law and viewed this project as the best means to influence any new legislation ». The 18 month program entails technical assistance to « support a revision of the 2011 decree-law of associations to ensure input from civil society and subject matter experts…».

Except that from the beginning, Tunisian civil society organizations were at odds with such intervention. Speaking with Nawaat, the DI team in Tunis described the ambiance during an initial meeting with the Ministry and a number of associations on March 30 this year as « hostile … We tried to hold a constructive dialogue, we didn’t want to go against what civil society wanted ». And so DI pulled together a committee of experts, a few of the original drafters of Decree-Law 88 including Chafik Sarsar, Slim Laghmani, Fawzi Ben Hammed and Ferhat Horchani, to come up with several possible options. After a second consultation organized by the Ministry on May 12 and a series of smaller meetings, civil society organizations and the Ministry agreed on a solution: a separate organic law would be promulgated creating a digital platform, in theory transforming a problematic paper-based administrative procedure into a more efficient and transparent electronic one.

The compromise reached was one of lukewarm acceptance, with associations never fully convinced of DI’s role or US intervention in the matter. According to Amine Ghali of the Kawakibi Center for Democratic Transition, this lingering reticence owes at least in part to the fact civil society organizations who had participated in the first national consultation believed they had more or less succeeded in putting off the government’s efforts to amend Decree-Law 88. That is, recalls Ghali, « until about a year ago, when the US began its project to improve it. This was not well received by civil society ». As Ghali and representatives of other organizations have argued since the first national consultation, « the problem is not in the text, but in its application ». From this standpoint, the agenda to « improve » the decree-law, in spite of its imperfections, opens the text up to more risks than it’s worth. He refers to initiatives taken to improve legislation in other domains, citing « the decree-law on audiovisual communication (HAICA), the decree-law on the fight against corruption…all the positive measures passed in 2011, as soon as we open them up to improvements, we end up with something worse ».

National Registry of Institutions, a new set of obligations for associations

The option to preserve Decree-Law 88 content was thus a relatively acceptable solution on all sides, with the Ministry, DI and associations on board to create a separate text setting up an online data base for associations. Discussions to this end were underway when news arrived that a similar platform under another department of government also intended to cover associative activities. Submitted to parliament by the Ministry of Justice on April 2 and passed on July 27, Draft-Law 30/2018 concerning the National Registry of Institutions lists associations among the economic actors required to report through its electronic data base. With the aim of « improving transparency of economic and financial transactions », the measure was swiftly pushed through to adoption in efforts to comply with an Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism report by the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in December 2017. Among its recommendations for Tunisia, the FATF « urged authorities to expedite the implementation of measures related to the development of the commercial register system ».

The FATF did not elaborate on what such a system would look like: the how and who was the impetus of the Tunisian government, which, as far as Ghali is concerned, used the FATF’s recommendation as an alibi to restrict civil society. « Why include associations? It’s a registry of commercial institutions, » he notes, before adding that it simply wasn’t logical for a separate ministry to be working on a platform that touched the sector, all the more so because it added obligations not present in Decree-Law 88. DI for its part calls the inclusion of associations in the National Registry « a little far-fetched », and describes the measure as « a masked transformation of the declaration regime for the creation of associations established by Decree-Law 88, to an authorization regime » in which the existence of associations is complicated by two discordant sets of reporting requirements.

With these points in mind, DI and civil society organizations alike scrambled to have the mention of associations removed from the draft law. Ghali recounts, « We did our best to lobby in a very short period of time with deputies, the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of Civil Society. We believed we had convinced them. » But at the last moment, Minister Mehdi Ben Gharbia evidently surprised everyone. During his hearing before the Commission of Agriculture, Commerce and Related Services in charge of examining the law, « he didn’t even stay neutral. He went to parliament and affirmed his support for the text » regrets Ghali

Opposition parties petition unconstitutionality

The hearing represented a game changer for associations, now convinced that the Ministry of Civil Society was pursuing its own agenda for the sector. One day before parliament moved to vote on the draft law, two dozen organizations including Jamaity, Kawakibi, Al Bawsala, the International Observatory of Associations and Sustainable Development (ASDI), Euromed Rights and Oxfam issued a press release, pointing to the draft law’s non-conformity with Article 65 of the constitution and calling out the « repressive nature of the draft law, which would effectively lead to an aversion to civic work and would affect the transformative role played by associations ». The press release was based on a note prepared by the committee of experts appointed by DI submitted their own petition, denouncing the draft law’s imposition of new obligations not included in Decree-Law 88 as well as « heavy sanctions » in contradiction with Article 49 of the constitution, and concluding that a viable solution for the purposes of transparency in the sector would be « the adoption of an organic law creating a platform dedicated to associations, and to not submit associations to the dispositions of the draft law on the National Registry of Institutions ».

To no avail. On July 27, draft law 2018/30 was passed without the amendment to remove associations from the registry. On August 2, thirty parliamentary deputies, mainly representing opposition party blocs and headed by Ghazi Chaouachi of Attayar (the Democratic Current), petitioned the measure on account of several unconstitutional provisions. Among the arguments presented to the Constitutional Court, deputies pointed out the law’s non-conformity with Articles 35 and 49 with provisions restricting the right to form associations and to exercise associative activities. Contacted by Nawaat, Chaouachi affirmed that deputies had consulted Chafik Sarsar regarding these points, and that they support the proposal to give Decree-Law 88 the status of an organic law through passing a separate text for a platform dedicated to associations.

With parliament on vacation and administration operating on a half-time summer schedule, the Constitutional Court has yet to respond to deputies’ appeal. For now, this means that efforts to « improve the regulatory environment » for associations in Tunisia are at a standstill. Amine Ghali remarks that « the idea to have a new text creating a platform is now obsolete. We can’t have two platforms, two sets of obligations for civil society ». As for Decree-Law 88, the fact that it remains untouched is, in his words, a « momentary glimmer of hope », amidst hints that a draft law for the sector is still floating around somewhere in Ministry drawers.

iThere are no comments

Add yours