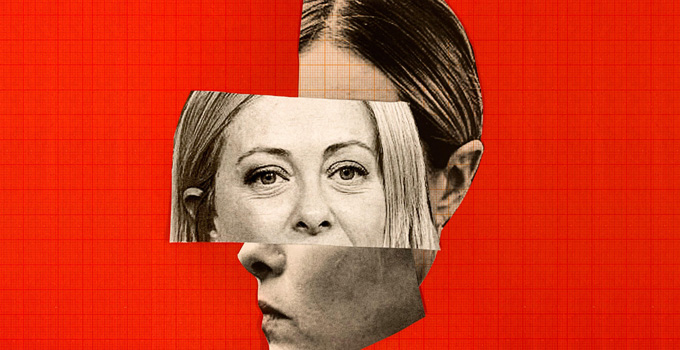

Between a Rock (Censorship) and a Hard Place (Prison)

By Hamid Skif

From Mauritania to Egypt, which borders with the Maghrib, not a day goes by without journalists being harassed because of their work. To mark the International Day of the Freedom of the Press, the Algerian journalist and author Hamid Skif sums up the situation.

Without a doubt, the Kafkaesque sentencing of journalist Ali Lmrabet to a ten year writing ban by a court of the first instance in the Moroccan capital, Rabat, is the event of the year. This was the culmination of a court case marred by irregularities. It also makes the intentions of the authorities clear, namely to silence Ali Lmrabet while he was waiting for authorisation to launch a new newspaper.

The motive for the charge brought against the journalist were his comments in the weekly newspaper al-Mustakil on the Sahraouis, who live in the Polisario camp in south western Algeria. He stated that the Sahraouis were not “locked up against their will”, as official statements would have the public believe, but were instead “refugees” according to the definitions of the United Nations.

Quite apart from the fact that the press campaign that was launched against him and the sit-ins organised by unknown organisations that branded him a traitor, legal proceedings were instituted against him in numerous cities across the kingdom. Given the passions aroused by the Western Sahara issue, this situation could have far-reaching consequences.

On 21 May 2003, Ali Lmrabet, the then editor-in-chief of Demain magazine and Douman, was sentenced to four years in prison for lese-majesty, assault on the territorial integrity of the state, and assault on the monarchy. This sentence was shortened to three years. In January 2004, he – along with other journalists – was pardoned by the King.

The situation in Algeria

In the neighbouring People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria, the managing editor of the now defunct daily newspaper Le Matin, Mohamed Benchicou, who has been in prison for two years now, has two other sentences to serve even though his defence lawyers expected him to be released on the grounds of poor health : three months without parole and two more months on top of that because a minister and a business man respectively instituted legal proceedings against him.

The same sentences were handed down on four former journalists from Le Matin and two other court cases are underway. The accusations on which these cases are founded include defamation, assault on the apparatus of the state (an accurate definition of what this actually means does not exist) and assault on or contempt of the head of state.

The reason for Mohamed Benchicou’s two-year prison sentence is obviously the fact that his newspaper launched an unrestrained campaign against the re-election of the president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika. Be that as it may, he was sentenced for the transfer of commercial papers (it must be said, however, that there is no law against sending receipts).

Mauritania and Tunisia

In Mauritania, the freelance journalist Mohamed Lemine Ould Mahmoud was released from prison in April. He spent a month in prison for interviewing a young woman who had been identified by an NGO as a runaway slave.

The following must be said about Tunisia, which is set to host the World Information Summit later this year : together with Colonel Gadaffi of Libya, the Tunisian regime holds the record for the longest imprisonment of journalists. Moreover, there is absolutely no freedom of the press in the country.

For example, the lawyer Mohammed Abou, who was imprisoned on 1 March of this year, is in solitary confinement in the El-Kef prison because he published two articles on the Internet : one on torture and one inviting the Israeli Prime Minister, General Ariel Sharon, who will attend the second half of the World Information Summit in Tunis this November. In this article, he compared the services rendered by the generals Ariel Sharon und Ben Ali. He can expect to get up to ten years in prison for doing so.

Hamadi Jebali, managing editor of the weekly newspaper of the integralist party Enahda Al-Fajr, who has been in prison since 1991, began another hunger strike on 9 April.

Jebali was imprisoned on 31 January 1991 and sentenced on the very same day to one year in prison for defamation, having published an article in which he called for the abolition of military courts. On 28 August 1992, he was sentenced to sixteen years in prison for membership of an illegal organisation and the intention to change the state.

However, it is Libya that holds the world record for the longest imprisonment of a journalist : Abdullah Ali al-Sanussi al-Darrat. Despite never having been charged or given a court case, he has been in prison since 1973. No-one knows anything about where he is being held or the state of his health.

In the same country, a 52-year-old bookseller from Tobrouk, Abdel Razak al-Mansouri, has been in prison. He was secretly brought to Tripoli for having published an article on a website in Great Britain criticising the government.

Regimes in the region only claim to support democracy

These cases are symbolic of a situation that can only be described as critical. No separation of powers and the exploitation of the judicial system make a farce of the democracy that the regimes in these countries claim to support. Despite the fact that real progress has been made, there is still an uphill climb ahead until freedom of the press becomes a reality in both Algeria and Morocco.

And these are the countries that have made the most progress in this area !

Algeria is not yet willing to permit private television and radio stations because the government resists any projects of this sort. In doing so, it is continuously breaking a law that was passed by the previous government. However, the same applies to the last government which, at least, put the law to the national assembly.

In the countries of the Maghrib, there are limits that may not be exceeded and areas that may not be touched upon : these areas include the president or the royal family, defence matters, army, and corruption.

In the case of corruption, this does not mean that it is forbidden to make general references to corruption, but that it is not permitted to provide hard facts and specific details. Nor is it permissible to write about the secret service or the private lives of the ruling class. Any journalist that sets about publishing facts and not just commenting on any of these issues, is putting a lot at stake. This is why the freedom to which many media refer is purely a matter of form.

However, this criticism does not reduce the courage of the journalists who find themselves between the rock of censorship and the hard place of prison, and are sometimes even harassed or, as was in the case in Algeria, put at the mercy of the bullets of the Integralists or in the clutches of those in power.

Tunisia – the only Maghrib country to censor the Internet

For example, the edition of the Mauritanian newspaper Le Calame was censored on 6 April because it mentioned the situation in the army. Hannibal, the only private television channel in Tunisia has just been refused access to the country’s stadia ; its sport programmes were becoming a serious competitor for the country’s two public channels. Moreover, Tunisia is the only country in the Maghrib that censors the Internet.

Of the 23 websites that cannot be accessed on Tunisian territory, ten are news sites, eight defend human rights, and five are the sites of political parties.

Nevertheless, it is important to mention the confusion felt by certain journalists. They are in the impossible situation of being obliged to keep the public informed while at the same time avoiding involvement in the intrigues of the ruling clans or their supporters.

During the presidential election campaign of 2004, parts of the Algerian press peppered their criticism of the presidential candidate with slander and gossip that had been spread by a military clan. In the course of these events several journalists were exposed. This will not be forgotten for some time to come.

In conditions such as these, better training and more respect for the journalistic ethos could put an end to the confusion of roles.

However, without a sound legal and economic basis, even this will not be sufficient. It would allow the media to free themselves from the burdens they currently carry in a sector that is incredibly slow when it comes to liberalisation.

Hamid Skif

Translation from German : Aingeal Flanagan

Source : Qantara.de 2005

iThere are no comments

Add yours