French colonialism in Tunisia did not only alter the political, economic, and social structures of the country. It also changed farming activities, environment, and most importantly, the agricultural structures and policies of the North African country.

Similar to other aspects of colonialism, agricultural colonialism endures. Indeed, its manifestations are apparent in Tunisia today. In this article, however, I only go back to the micro-foundations of France’s agricultural colonialism in the country. These micro-foundations are found in the writings of French colonists such as Robert Wastelier and Charles Géniaux, among many others.

Restoring the Roman legacy

French colonists’ writings echo Metropolitan France’s “colonial fantasies” in Tunisia, particularly, the idea of restoring the Roman legacy.

The historical imagery of Rome and Carthage are critical to the French colony’s historical narrative, which carefully selects the story to be old in order to legitimize France’s agricultural “mission civilisatrice,” or “civilizing mission,” in Tunisia.

In French colonial writings, Roman Tunisia and Carthage are portrayed as a fertile setting where agriculture brought prosperity. Robert Wastelier, Charles Géniaux and many other French colonists offered detailed ecological descriptions of Tunisia, to which they often referred as “the granary of Rome.”

In a report written in 1903 by Robert Wastelier and published in Lille under the title “Etude sur la colonisation en Tunisie,” we read the following passage:

Elle a des terres fertiles et salubres. Ce fut autrefois la plus riche Province riveraine de la Méditerranée. On l’avait appelée le grenier de Rome…C’est à nous à recommencer ce qu’ont fait les Romains.

No doubt, the French colonial narrative places all the blame on Tunisia’s “uncivilized Arabs and Berbers” for leaving behind the glory of Carthage and Rome. This narrative depicts the role of the French as a mere restoration mission of a forgotten legacy in Tunisia.

To romanticize the restoration mission more, in “Etude Sur La Colonisation En Tunisie” Wastelier reminds his compatriots of Gustave Flaubert’s “Salammbo,” a historical novel set in ancient Carthage:

C’est là que fleurit Carthage, dont notre éminent romancier Flaubert a évoqué les splendeurs dans son bel ouvrage de Salambo.

The theory and practice of agricultural colonialism

To expand the colonial dynamics in agriculture, French colonists studied Tunisia’s ecology of farming and environment and later on institutionalized agricultural colonialism.

According to some French colonists, colonialism was a vocation. Among those who held such a view was Charles Géniaux, an author who settled in Tunisia and wrote a ‘colonial manual’ entitled “Comment on devient Colon.” In his pamphlet, published in Paris in 1908, he asserts that colonialism is a “difficult vocation” and that a colonist has to have extensive knowledge of the colony:

La colonisation est un métier qui s’apprend comme les autres; c’est même un métier plus difficile, car il est complexe et il oblige le colon à posséder une science étendu.

Géniaux shares an anecdote to draw attention to the importance of knowing the colony before moving to it.

The writer met a Frenchman who was planning to move to Tunisia or Algeria to invest in agricultural activities like other colonists. He asked the man if he knew the agricultural sectors and regions of those colonies but the latter appeared ignorant. He humorously ended the conversation saying that he would become a cowboy there and it would be fun!

[Géniaux] Quelle profession voulez-vous donc exercer avec cet équipement ?

[French man] Je vais coloniser.

[Géniaux] Coloniser? Dans quelle branche et en quelle région?

[French man] Enfin être colon, voilà tout! En Algérie ou en Tunisie, je ne sais pas encore…cela dépendra des occasions…si l’on m’offre une bonne affaire…

[Géniaux] Une bonne affaire, en quoi?

[French man] En quoi? Comme vous êtes curieux, monsieur! Mais en n’importe quoi…d’avantageux…Viticulteur! Oléiculteur…je deviendrai un cow-boy, ce serait amusant!

After such observations and encounters, Géniaux decided to take on the task of informing his compatriots about Tunisia through “Comment on devient Colon.”

Apparently, Charles Géniaux believed in the dictum “knowledge is power.” For him, a colonist’s knowledge of Tunisia would set the ground for a better exploitation of resources and fertile lands of the “granary of Rome.” In his pamphlet, he looks at different aspects of Tunisia’s agriculture, the ecology of farming, and the labor force that French masters would later exploit.

Both Charles Géniaux and Robert Wastelier offered a detailed description of Tunisia’s agricultural regions and climates. Théier efforts aimed both to inform the French colonists about a new land of colonial opportunities and to encourage them to populate it. This would ensure that the French outnumber the Italians who were already engaged in agricultural activities in Tunisia.

Géniaux mentions several regions and their agricultural hallmarks. He informs his compatriots that inhabitants of Sfax are specialized in olive cultivation, and that Béja’s residents have fertile wheat fields. He advises his fellow colonists to visit La Mornagia and L’oued Zarga where there was an association of French colonists, L’association des colons français de la Mornagia.

Similarly, R. Wastelier informs French colonists about Tunisia’s appealing climate:

Au point de vue du climat…La Tunisie, dont les vallées sont largement ouvertes aux brises marines, jouit d’une température plus régulière, plus douce et moins sèche que sa voisine de l’Ouest.

Likewise, reports sent in the 1880’s from explorer Henri Duveyrier to Paul Cambon, then Resident-General in Tunisia, portray the country as the best place for colonists to recreate the French habitat. For Duveyrier, the north of Tunisia and its coastal regions are “better than the southern regions of Europe.”

Lastly, Wastelier reminds French agricultural colonists of the natural resources that will be at their disposal once they arrive in “the granary of Rome”:

Les ressources de la Tunisie pour la culture sont variées…Le sol…se prête à toutes les productions: Les céréales, la vigne…l’olivier, l’oranger…

Along with the theoretical aspects of French agricultural colonialism in Tunisia, there was an institutional aspect at play. To concretize their ambitions, French colonists established several agricultural schools with the aim of producing well trained French colonists who would later exploit the colony’s natural resources.

The schools were established in Metropolitan France and its colonies. In the 12th issue of the periodical “La Dépêche Coloniale,” published in 1909, we read a lengthy article on the technologies, laboratories, and agricultural techniques used in what the French called the “Jardin colonial,” literally the “Colonial Garden.”

In 1898, the French established L’école coloniale d’agriculture de Tunis among other colonial agricultural institutions and associations. The school opened its doors to French students from Metropolitan France where other colonial institutions, such as L’école supérieure d’agriculture coloniale, were established.

French students were offered the chance to continue their training in colonial schools outside Metropolitan France where they received theoretical and practical agricultural education. The aim of this training was to prepare, in Géniaux’s words, “des colons agriculteurs,” or agricultural colonists:

Il faut donc que les élèves de Nantes passent la mer dès la seconde année et viennent demander à l’Ecole Coloniale de Tunis l’enseignement complet et véritable qui fera d’eux des agriculteurs…L’Ecole de Tunis…s’adresse aux jeunes gens qui désirent s’établir comme colons agriculteurs.Charles Géniaux

After Tunisia’s independence, L’école coloniale d’agriculture de Tunis became L’école supérieure d’agriculture de Tunis (ESAT). It is currently called L’institut national agronomique de Tunisie (INAT).

Colonial production and local farmers

The arrival of French colonial farmers changed the nature of agricultural production in Tunisia. For example, viticulture gained momentum beginning in 1886 and according to some sources, reached, 2000 hectares that same year. By 1956, 25.000 hectares of Tunisian fertile lands were devoted to viticulture.

Viticulture boosted France’s wine production and was accompanied by the deterioration of living standards of Tunisian farmers. The “khammes” who were working for the French, were exhausted by their masters’ taxes and the new agricultural policies. They lived in gourbis (stick shacks) and received “some seeds and capital.”

This, however, was not enough to modernize or improve Tunisian farmers’ agricultural techniques and equipment. Thus, small farmers did not in fact have access to genuine agricultural credits as pointed out by Lisa Anderson.

Currently, some regions and agricultural sectors in Tunisia are structurally affected by the colonial past. This fact calls for the implementation of new agricultural strategies by policy makers.

Moreover, some current problems in the agriculture sector, such as issues relating to Jemna’s oases, suggest that the independent state has failed to manage former colonial territories in some parts of the country.

Notes

- Publications of Charles Géniaux and Robert Wastelier are retrieved from Bibliothèque nationale de France.

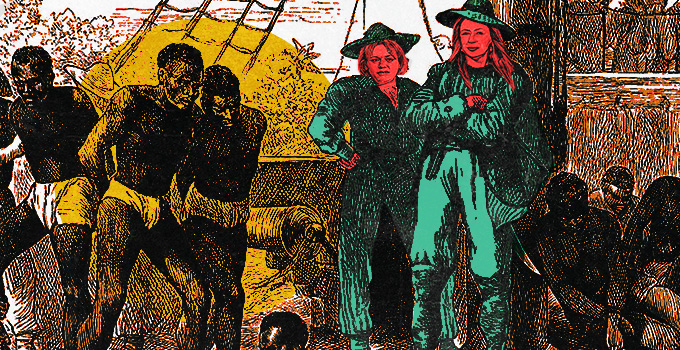

- The images in this article are retrieved from: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- I was mindful of Meyda Yegenoglu’s book: Colonial Fantasies in coming up with the title of this article.

I truly fail to see the effect of colonial tradition on the current situation in the country. It seems to me that you are rather narrating few historical facts which is ok, but I am not sure if I was a policy maker I would know which direction I should go to tailor the current farming tradition to the real needs of the population, baring in mind of course an international market etc….

Many thanks for your comment.

-The colonial tradition left the country with what is called the “colonial domain”, it consists of lands which were once exploited by the French. The sectors and agricultural activities of those lands did not change since then or their production does not meet any economic needs. Also, the ownership of those lands is still a problematic issue until today and i referred to Jemna as the most current example of such cases.

-I hope you found the “few historical facts” interesting =)

More articles about Tunisia in English please. Keep it up and thank you for the informations you provided!